People with mechanical heart valves need blood thinners on a daily basis because they have a higher risk of blood clots and stroke. Researchers at the ARTORG Center of the University of Bern, Switzerland, now identified the root cause of blood turbulence leading to clotting. Design optimization could greatly reduce the risk of clotting and enable these patients to live without life-long medication.

Most people are familiar with turbulence in aviation: certain wind conditions cause a bumpy passenger flight. But even within human blood vessels, blood flow can be turbulent. Turbulence can appear when blood flows along vessel bends or edges, causing an abrupt change in flow velocity. Turbulent blood flow generates extra forces that increase the odds of blood clots to form. These clots grow slowly until they may be carried along by the bloodstream and cause stroke by blocking an artery in the brain.

Mechanical heart valves produce turbulent blood flows

{module INSIDE STORY}Patients with artificial heart valves are at a higher risk of clot formation. The elevated risk is known from the observation of patients after the implantation of an artificial valve. The clotting risk factor is particularly severe for the recipients of mechanical heart valves, where the patients must receive blood thinners every day to combat the risk of stroke. So far, it is unclear why mechanical heart valves promote clot formation far more than other valve types, e.g. biological heart valves.

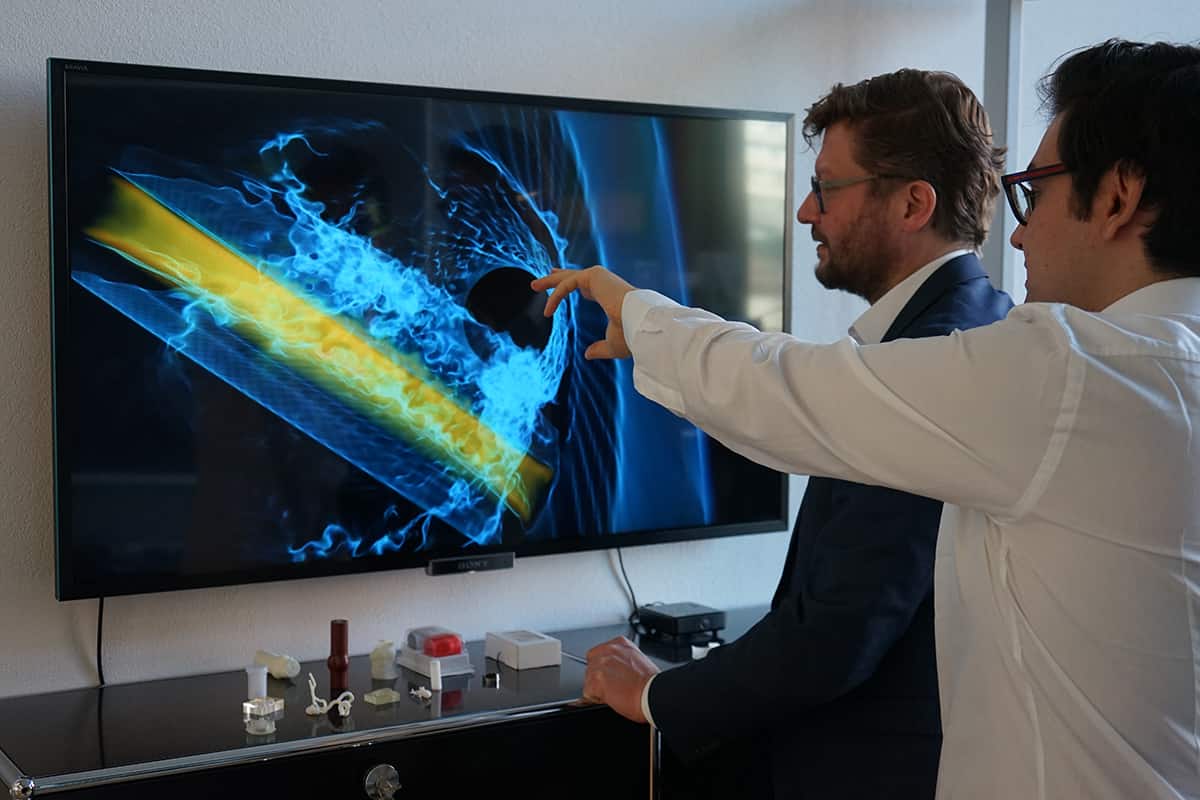

A team of engineers from the Cardiovascular Engineering Group at the ARTORG Center for Biomedical Engineering Research at the University of Bern has now successfully identified a mechanism that can significantly contribute to clot formation. They used complex mathematical methods of hydrodynamic stability theory, a subfield of fluid mechanics, which has been used successfully for many decades to develop fuel-efficient aircraft. This is the first translation of these methods, which combine physics and applied mathematics, into medicine.

Using complex computer simulations on flagship supercomputers at the Centro Svizzero di Calcolo Scientifico in Lugano, the research team was able to show that the current shape of the flow-regulating flaps of the heart valve leads to strong turbulence in the blood flow. "By navigating through the simulation data, we found how the blood impinges at the front edge of the valve flaps, and how the blood flow quickly becomes unstable and forms turbulent vortices," explains Hadi Zolfaghari, first author of the study. "The strong forces generated in this process could activate the blood coagulation and cause clots to form immediately behind the valve. Supercomputers helped us to capture one root cause of turbulence in these valves, and hydrodynamic stability theory helped us to find an engineering fix for it."

The mechanical heart valves which were used in the study consist of a metal ring and two flaps rotating on hinges; the flaps open and close in each heartbeat to allow blood to flow out of the heart but not back in again. In the study, the team also investigated how the heart valve could be improved. It showed that even a slightly modified design of the valve flaps allowed the blood to flow without generating instabilities which lead to turbulence – more like a healthy heart. Such a blood flow without turbulence would significantly reduce the chance of clot formation and stroke.

Life without blood thinners?

More than 100,000 people per year receive a mechanical heart valve. Because of the high risk of clotting, all these people must take blood thinners, every day, and for the rest of their lives. If the design of the heart valves is improved from a fluid mechanics point of view, it is conceivable that recipients of these valves would no longer need blood thinners. This could lead to normal life – without the lasting burden of receiving blood thinner medication. "The design of mechanical heart valves has hardly been adapted since their development in the 1970s," says Dominik Obrist, head of the research group at the ARTORG Center. "By contrast, a lot of research and development has been conducted in other engineering areas, such as aircraft design. Considering how many people have an artificial heart valve, it is time to talk about design optimizations also in this area in order to give these people a better life."

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?