An international team of astronomers used a database combining observations from the best telescopes in the world, including the Subaru Telescope, to detect the signal from the active supermassive black holes of dying galaxies in the early Universe. The appearance of these active supermassive black holes correlates with changes in the host galaxy, suggesting that a black hole could have far-reaching effects on the evolution of its host galaxy.

The Milky Way Galaxy where we live includes stars of various ages, including stars still forming. But in some other galaxies, known as elliptical galaxies, all of the stars are old and about the same age. This indicates that early in their histories elliptical galaxies had a period of prolific star formation that suddenly ended. Why this star formation ceased in some galaxies but not others are not well understood. One possibility is that a supermassive black hole disrupts the gas in some galaxies, creating an environment unsuitable for star formation.

To test this theory, astronomers look at distant galaxies. Due to the finite speed of light, it takes time for light to travel across the void of space. The light we see from an object 10 billion light-years away had to travel for 10 billion years to reach Earth. Thus the light we see today shows us what the galaxy looked like when the light left that galaxy 10 billion years ago. So looking at distant galaxies is like looking back in time. But the intervening distance also means that distant galaxies look fainter, making study difficult.

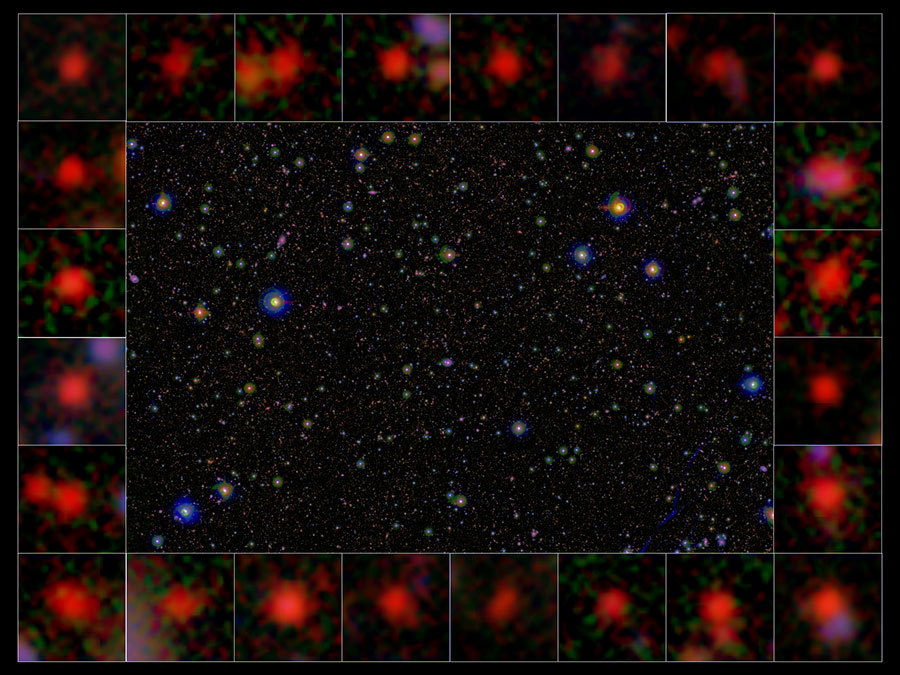

To overcome these difficulties an international team led by Kei Ito at SOKENDAI in Japan used the Cosmic Evolution Survey (COSMOS) to sample galaxies 9.5-12.5 billion light-years away. COSMOS combines data taken by world-leading telescopes, including the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Subaru Telescope. COSMOS includes radio waves, infrared light, visible light, and x-ray data.

The team first used optical and infrared data to identify two groups of galaxies: those with ongoing star formation and those where star formation has stopped. The x-ray and radio wave data signal-to-noise ratio was too weak to identify individual galaxies. So the team combined the data for different galaxies to produce higher signal-to-noise ratio images of “average” galaxies. In the averaged images, the team confirmed both x-ray and radio emissions for the galaxies without star formation. This is the first time such emissions have been detected for distant galaxies more than 10 billion light-years away. Furthermore, the results show that the x-ray and radio emissions are too strong to be explained by the stars in the galaxy alone, indicating the presence of an active supermassive black hole. This black hole activity signal is weaker for galaxies where star formation is ongoing.

These results show that an abrupt end in star formation in the early Universe correlates with increased supermassive black hole activity. More research is needed to determine the details of the relationship.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?