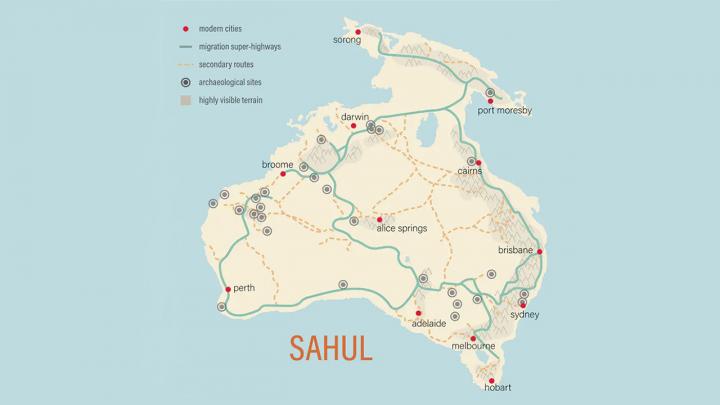

The best path across the desert is rarely the straightest. For the first human inhabitants of Sahul -- the super-continent that underlies modern Australia and New Guinea -- camping at the next spring, stream, or rock shelter allowed them to thrive for hundreds of generations. Those who successfully traversed the landmarks made their way across the continent, spreading from their landfall in the Northwest across the continent, making their way to all corners of Australia and New Guinea.

By simulating the physiology and decisions of early way-finders, an international team of archaeologists, geographers, ecologists, and computer scientists has mapped the probable "superhighways" that led to the first peopling of the Australian continent some 50,000-70,000 years ago. Their study is the largest reconstruction of a network of human migration paths into a new landscape. It is also the first to apply rigorous computational analysis at the continental scale, testing 125 billion possible pathways.

"We decided it would be really interesting to look at this question of human migration because the ways that we conceptualize a landscape should be relatively steady for a hiker in the 21st century and a person who was way-finding into a new region 70,000 years ago," says archaeologist and computational social scientist Stefani Crabtree, who led the study. Crabtree is a Complexity Fellow at the Santa Fe Institute and Assistant Professor at Utah State University. "If it's a new landscape and we don't have a map, we're going to want to know how to efficiently move throughout a space, where to find water, and where to camp -- and we'll orient ourselves based on high points around the lands."

"One of the really big unanswered questions of prehistory is how Australia was populated in the distant past. Scholars have debated it for at least a hundred and fifty years," says co-author Devin White, an archaeologist and remote sensing scientist at Sandia National Laboratories. "It is the largest and most complex project of its kind that I'd ever been asked to take on."

To re-create the migrations across Sahul, the researchers first needed to simulate the topography of the supercontinent. They "drained" the oceans that now separate mainland Australia from New Guinea and Tasmania. Then, using hydrological and paleo-geographical data, they reconstructed inland lakes, major rivers, promontory rocks, and mountain ranges that would have attracted the gaze of a wandering human.

Next, the researchers programmed in-silico stand-ins for human travelers. The team adapted an algorithm called "From Everywhere to Everywhere," created by White, to program the way-finders based on the caloric needs of a 25-year-old female carrying 10 kg of water and tools.

The researchers imbued these individuals with the realistic goal of staying alive, which could be achieved by finding water sources. Like backcountry hikers, the digital travelers were drawn to prominent landmarks like rocks and foothills, and the program exacted a caloric toll for activities such as hiking uphill within the artificial landscape.

When the researchers "landed" the way-finders at two points on the coast of the re-created continent, they began to traverse it, using landmarks to navigate in search of fresh water. The algorithms simulated a staggering 125 billion possible pathways, run on a Sandia supercomputer, and a pattern emerged: the most-frequently traveled routes carved distinct "superhighways" across the continent, forming a notable ring-shaped road around the right portion of Australia; a western road; and roads that transect the continent. A subset of these superhighways map to archaeological sites where early rock art, charcoal, shell, and quartz tools have been found.

"Australia's not only the driest, but it's also the flattest populated continent on Earth," says co-author Sean Ulm, an archaeologist and Distinguished Professor at James Cook University. Ulm is also Deputy Director of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage (CABAH), whose researchers contributed to the project. "Our research shows that prominent landscape features and water sources were critical for people to navigate and survive on the continent. In many Aboriginal societies, landscape features are known to have been created by ancestral beings during the Dreaming. Every ridgeline, hill, river, beach, and water source is named, storied, and inscribed into the very fabric of societies, emphasizing the intimate relationship between people and place. The landscape is woven into peoples' lives and their histories. It seems that these relationships between people and Country probably date back to the earliest peopling of the continent."

The results suggest that there are fundamental rules humans follow as they move into new landscapes and that the researchers' approach could shed light on other major migrations in human history, such as the first waves of migration out of Africa at least 120,000 years ago.

Future work, Crabtree says, could inform the search for undiscovered archaeological sites, or even apply the techniques to forecast the movements of human migration shortly, as populations flee drowning coastlines and climate disruptions.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?