ACADEMIA

After 25 years, sustainability is a growing science that's here to stay

Published researchers doubling every eight years; research centers globally dispersed, not centralized

Sustainability has not only become a science in the past 25 years, but it is one that continues to be fast-growing with widespread international collaboration, broad disciplinary composition and wide geographic distribution, according to new research from Los Alamos National Laboratory and Indiana University.

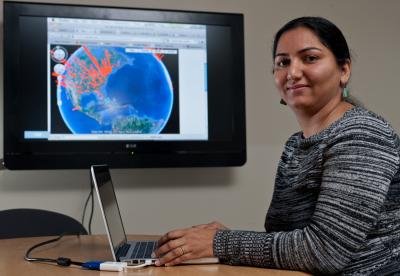

The findings, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, were assembled from a review of 20,000 academic papers written by 37,000 distinct authors representing 174 countries and over 2,200 cities. Authors of the paper, Los Alamos research scientist Luís M. A. Bettencourt, and Jasleen Kaur, a Ph.D. student in Indiana University Bloomington's School of Informatics and Computing, also identified the most productive cities for sustainability publications and estimated the field's growth rate, with the number of distinct authors doubling every 8.3 years. The study covered research generated from 1974 through 2010.

By analyzing the temporal evolution (distinct authors), geographic distribution, the discipline's footprint within traditional scientific disciplines, the structure and evolution of sustainability science's collaboration network, and the content of the publications, the authors ascertained that the field "has indeed become cohesive over the last decade, sharing large-scale collaboration networks to which most authors now belong and producing a new conceptual and technical unification that spans the globe."

While specialized fields like the natural sciences have generally been concentrated in a few cities in developed nations, Bettencourt and Kaur found that sustainability science had a very different geographic footprint.

"The field is widely distributed internationally and has a strong presence not only in nations with traditional strength in science -- the U.S., Western Europe and Japan -- but also elsewhere," Kaur said. "It is also perhaps surprising that the world's leading city in terms of publications in the field is Washington, D.C., outpacing the productivity of Boston or the Bay Area, which in other fields are several fold greater than that of the U.S. capital."

Countries producing sustainability publications of noteworthy magnitude were Australia, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Brazil, China, India, South Africa, Nigeria, Kenya and Turkey. Productive cities included London, Stockholm, Wageningen in the Netherlands, Seattle, and Madison, Wis.

When they dissected the discipline's footprint with respect to other fields contributing to sustainability science, social sciences accounted for 34 percent of the output, followed by biology with 23. 3 percent and engineering at 21.6 percent. Within each of those leading fields, the authors then identified leading subfields in each group: Environmental policy was 20.2 percent of the social science output; weed management was 16.8 percent of the biology total; soil science was 23.6 percent of the engineering total.

The authors also found that sustainability science had a strong presence in smaller universities and laboratories and that the field had received support from cities and nations that transcended locations more commonly recognized in terms of strength of scientific production.

"The presence of political and economic capitals, rather than traditionally more academic places is a common trend throughout the world," the paper noted. Regional centers with high production included Nairobi, Cape Town, Beijing, Melbourne and Tokyo.

"We believe that all of this evidence, when taken together, establishes the case for the existence of a young and fast-growing unified scientific practice of sustainability science," Kaur said. "And it bodes well for its future success at facing some of humanity's greatest scientific and societal changes."