ACADEMIA

NASA paper paves way to more sophisticated modeling of magnetosphere

On April 5, 2010, the sun spewed a two million-mile-per-hour stream of charged particles toward the invisible magnetic fields surrounding Earth, known as the magnetosphere. As the particles interacted with the magnetic fields, the incoming stream of energy caused stormy conditions near Earth. Some scientists believe that it was this solar storm that interfered with commands to a communications satellite, Galaxy-15, which subsequently foundered and drifted, taking almost a year to return to its station.

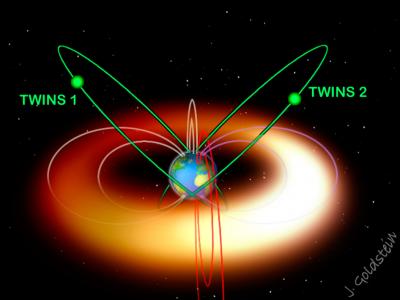

To better understand how to protect satellites from intense bursts of energy from the sun, scientists study the full chain of space weather events from first eruptions on the sun to how the magnetic fields around Earth compress and change shape in response. During the April 5 storm, two NASA Heliophysics System Observatory missions – the Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) and two spacecraft called the Two Wide-Angle Imaging Neutral-Atom Spectrometers (TWINS) – were perfectly positioned to view the storm from complementary viewpoints.

The three sets of instruments have been used together to paint a more complete picture of what happens during a solar storm, from initial impact of solar energy through to the particles that ultimately slide down into Earth's atmosphere near the poles. These results were published online on March 27, 2012 in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

"One spacecraft can only take recurring measurements along its own flight path," says Natalia Buzulukova, one of the authors on this paper and a geospace scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. and at the University of Maryland in College Park. "But this is not always enough to understand the whole event. With several spacecraft at once we have a unique opportunity to observe more of the magnetosphere simultaneously."

The two TWINS spacecraft and IBEX orbit Earth in very different paths. TWINS travels along a highly elliptical orbit around Earth through the magnetosphere. IBEX, too, circles Earth, but generally lies outside the magnetosphere allowing it to map the very edges of the solar system. Together, they offer glimpses from the inside and outside of the magnetosphere, including the side that faces the sun, the side that extends long away from the sun – the magnetotail -- and an electric current that sometimes appears around Earth like a giant hula hoop called the ring current.

"This imaging gives us a better global picture of the evolution of the magnetosphere — especially of the processes by which the sun injects energy into the magnetosphere — than has ever been available before," says David McComas, a space scientist at Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, who is first author on this paper and also the principal investigator for the IBEX and TWINS missions.

IBEX and TWINS both have instruments to study what's called energetic neutral atoms or ENAs. These fast moving particles are produced during particle collisions between charged and neutral particles. Crucially, they move in a straight line from their point of origin, unmolested by the magnetic fields that would constrain charged particles in their travels. Thus they can provide an "image" to decode and map out the structure of a far away charged particle system, such as occurs in the magnetosphere and ring current.

The ENA images from IBEX were taken from a distance of around 180,000 miles above the magnetosphere. They show that the magnetosphere immediately compressed under the impact of the charged particles from the solar wind. Minutes later, one of the TWINS spacecraft observed changes in the inner magnetosphere from a much-closer 28,000 miles: the ring current began to trap incoming charged particles. About 15 minutes after impact, these trapped particles gyrated down magnetic field lines into Earth's atmosphere, a process known as "precipitation." The time delay between the onset of trapped particles and losing them to the atmosphere points to a fairly slow set of internal processes carrying the region from storm impact through compression to precipitation.

"The solar storm directly causes the ring current activity, but the other effects, including particles precipitating down toward the atmosphere, are triggered by something called a substorm, a process that releases energy form the magnetotail," says Buzulukova. "These two triggers have different physics and different manifestations. This analysis opens the door to understanding how these different effects are connected."

The paper also paves the way to more sophisticated modeling techniques of the entire magnetosphere. To produce the new images, the team developed a series of techniques to process the imaging data, including improved procedures for differential background subtraction, "statistical smoothing" of images, and comprehensive modeling of the ring current.

"Understanding how solar events develop and impact satellites is like understanding the processes that cause extreme weather events on Earth to develop and destroy homes and businesses," says McComas. "Engineers use weather data to know where and how they need to strengthen buildings against various types of weather threats. The more we know about the processes occurring in space, the better engineers can design satellites to protect them from space weather hazards, which is increasingly important in our highly technological world."