ACADEMIA

Bato uses data assimilation for eruption forecasting

Geoscientists are learning how to better predict volcanic eruptions using GPS and the same method that helps forecast the weather

Volcanologists are beginning to use satellite measurements and mathematical methods to forecast eruptions and to better understand how volcanoes work, shows a new article in Frontiers in Earth Science.

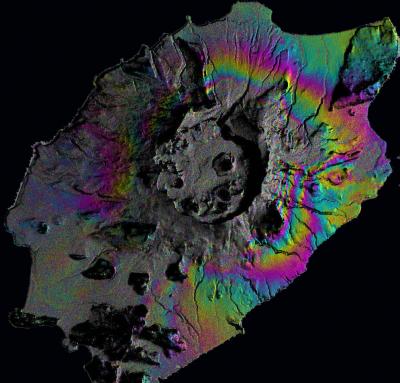

As magma shifts and flows beneath the earth's surface, the ground above flexes and quivers. Modern satellite technologies, similar to GPS, can now track these movements, and geoscientists are beginning to decipher what this reveals about what's happening underground--as well as what is likely to happen in the future.

"We're the first to have developed a strategy using data assimilation to successfully forecast the evolution of magma overpressures beneath a volcano using combined ground deformation datasets measured by Global Navigation Satellite System (more commonly known as GPS) and satellite radar data," explains Mary Grace Bato, lead author of the study and a researcher at the Institut des Sciences de la Terre (ISTerre) in France.

Bato and her collaborators are among the first to test whether data assimilation, a method used to incorporate new measurements with a dynamical model, can also be applied in volcano studies to make sense of such satellite data. Meteorologists have long used a similar technique to integrate atmospheric and oceanic measurements with dynamical models, allowing them to forecast the weather. Climate researchers have also used the same method to estimate the long-term evolution of the climate due to carbon emissions. But volcanologists are just beginning to explore whether the technique can also be used to forecast volcanic eruptions.

"The amount of satellite and ground-based geodetic data (i.e. GPS data) has tremendously increased recently," says Bato. "The challenge is how to use these data efficiently and how to integrate them with models in order to have a deeper understanding of what occurs beneath the volcano and what drives the eruption so that we can determine near-real-time and accurate predictions of volcanic unrest."

In their latest research, Bato and her colleagues have begun answering these questions by simulating one type of volcano--those which erupt with limited "explosivity" due to the build-up of underlying magma pressure. Through their exploratory simulations, Bato was able to correctly predict the excess pressure that drives a theoretical volcanic eruption, as well as the shape of the deepest underground magma reservoir and the flow rate of magma into the reservoir. Such reservoirs are typically miles below the surface and, as such, they're nearly impossible to study with existing methods.

Geoscientists still need to improve current volcanic models before they can be widely applied to real-life volcanoes, but Bato and her colleagues are already beginning to test their methods on the Grímsvötn Volcano in Iceland and the Okmok Volcano in Alaska. They believe that their strategy will be a key step towards more accurate predictions of volcanic behavior.

"We foresee a future where daily or even hourly volcanic forecasts will be possible--just like any other weather bulletin," says Bato.

This research is part of a broader collection of articles focused on volcanic hazard assessment.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?