ACADEMIA

French team uses supercomputer modeling to study how far plastic drifts far from its starting point as it sinks into the sea

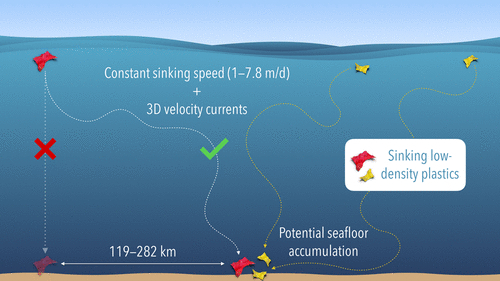

Discarded or drifting in the ocean, plastic debris can accumulate on the water’s surface, forming floating garbage islands. Although it’s harder to spot, researchers suspect a significant amount also sinks. In a new study in ACS’ Environmental Science & Technology, one team used supercomputer modeling to study how far bits of lightweight plastic travel when falling into the Mediterranean Sea. Their results suggest these particles can drift farther underwater than previously thought.

Plastic pollution is besieging the oceans from old shopping bags to water bottles. Not only is this debris unsightly, but animals can also become trapped or mistakenly eat it. And if it remains in the water, plastic waste can release organic pollutants. The problem is most visible on the surface, where currents can aggregate this debris into massive garbage patches. However, plastic waste also collects much deeper. Even material that weighs less than water can sink as algae and other organisms glom onto it, and through other processes. Bits of this light plastic, typically measuring 5 millimeters or less, have turned up at least half a mile below the surface. Researchers don’t know much about what happens when plastic sinks, but they generally assume it falls straight down from the surface. However, Alberto Baudena and his colleagues suspected this light plastic might not follow such a direct route.

To test this assumption, they used an advanced supercomputer model developed to track plastic at sea and incorporated extensive data already collected on floating plastic pollution in the Mediterranean Sea. They then simulated nearly 7.7 million bits of plastic distributed across the sea and tracked their virtual paths to depths as great as about half a mile. Their results suggested that the slower the pieces sank, the farther currents carried them from their points of origin, with the slowest traveling an average of roughly 175 miles laterally. While observations of the distribution of plastic underwater is limited, the team found their simulations agree with those available in the Mediterranean. Their simulations also suggested that currents may push plastic toward coastal areas and that only about 20% of pollution near coasts originates from the nearest country. According to the researchers, these particles’ long journeys mean this plastic has greater potential to interact with, and harm, marine life.

The authors acknowledge funding from the International Union for Conservation of Nature, the Tara Expeditions Foundation, and the Albert II Monaco Foundation.