BIG DATA

Together, humans, supercomputers figure out the plant world

Special issue of Applications in Plant Sciences looks at how researchers are using bioinformatics to understand plant form

As technology advances, science has become increasingly about data—how to gather it, organize it, and analyze it. The creation of key databases to analyze and share data lies at the heart of bioinformatics, or the collection, classification, storage, and analysis of biochemical and biological information using supercomputers. The tools and methods used in bioinformatics have been instrumental in the development of fields such as molecular genetics and genomics. But, in the plant sciences, bioinformatics and biometrics are employed in all fields — not just genomics — to enable researchers to grapple with the rich and varied data sources at their disposal.

In July 2013, Surangi Punyasena of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Selena Smith of the University of Michigan organized a special session at Botany 2013, the annual meeting of the Botanical Society of America in New Orleans, Louisiana. They invited plant morphologists, systematists, and paleobotanists, as well as computer scientists, applied mathematicians, and informaticians—all of whom were united in their interest in developing or applying novel biometric or bioinformatic methods to the form and function of plants. The goal: to provide a forum for a cross-disciplinary exchange of ideas and methods on the theme of the quantitative analysis of plant morphology.

As Punyasena explains, "The quantitative analysis of morphology is the next frontier of bioinformatics. Humans are very good at learning to recognize shape and texture, but there are many problems where accuracy and consistency are difficult to achieve with only expert-derived, qualitative data, and in many fields there are often a limited number of experts trained in these visual assessments."

The results of that session, along with invited papers, are published in the August issue of Applications in Plant Sciences as a special issue on Bioinformatic and Biometric Methods in Plant Morphology. Morphology is, of course, the study of form, and form as represented in this collection of articles has a broad scope—from microscopic pollen grains and charcoal particles, to macroscopic leaves and whole root systems. The methods presented in the issue, both recent and emerging, are varied as well, including automated classification and identification, geometric morphometrics, and skeleton networks, as well as tests of the limits of human assessment.

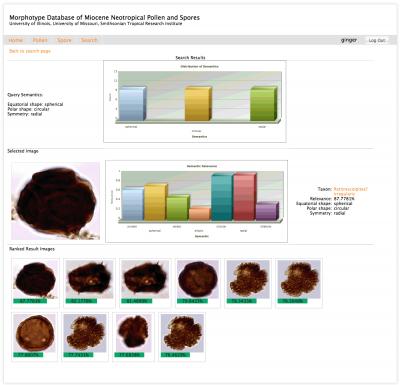

Three articles in the issue look at the application of biometric and bioinformatic methods in palynology: Han et al. (2014) introduce an online Miocene pollen database with semantic image search capabilities; Holt and Bebbington (2014) test the applications of an automated pollen classifier; and Mander et al. (2014) analyze differences in human and automated classification of grass pollen based on surface textures. Other papers highlight how biometric and bioinformatic methods apply to plants more broadly, including using skeleton networks to examine plant morphology such as roots (Bucksch, 2014), improving the quantification of geometric leaf shape metrics with a new protocol to measure leaf circularity (Krieger, 2014), comparing human and automated methods of quantifying aspects of leaf venation (Green et al., 2014), and applying morphometrics to charcoalified plant remains (Crawford and Belcher, 2014).

Taken as a whole, the issue presents a compelling argument for the importance of both computational and morphometric approaches.

"I think that there's been a renaissance in morphometric approaches," notes Punyasena. "New techniques are using easy access to high-quality digital imaging, powerful computers, and advances in computational analyses like machine learning to rethink the way we gather and analyze morphological data."

As advances in technology allow researchers to gather more and more morphological and image-based data, it has become increasingly important to be able to analyze and interpret those data quickly, accurately, consistently, and objectively. Biometric and bioinformatic methods make this possible, and reveal the potential of data collected from the shape and form of plants to be as rich of a data source as genetic data.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?