PROCESSORS

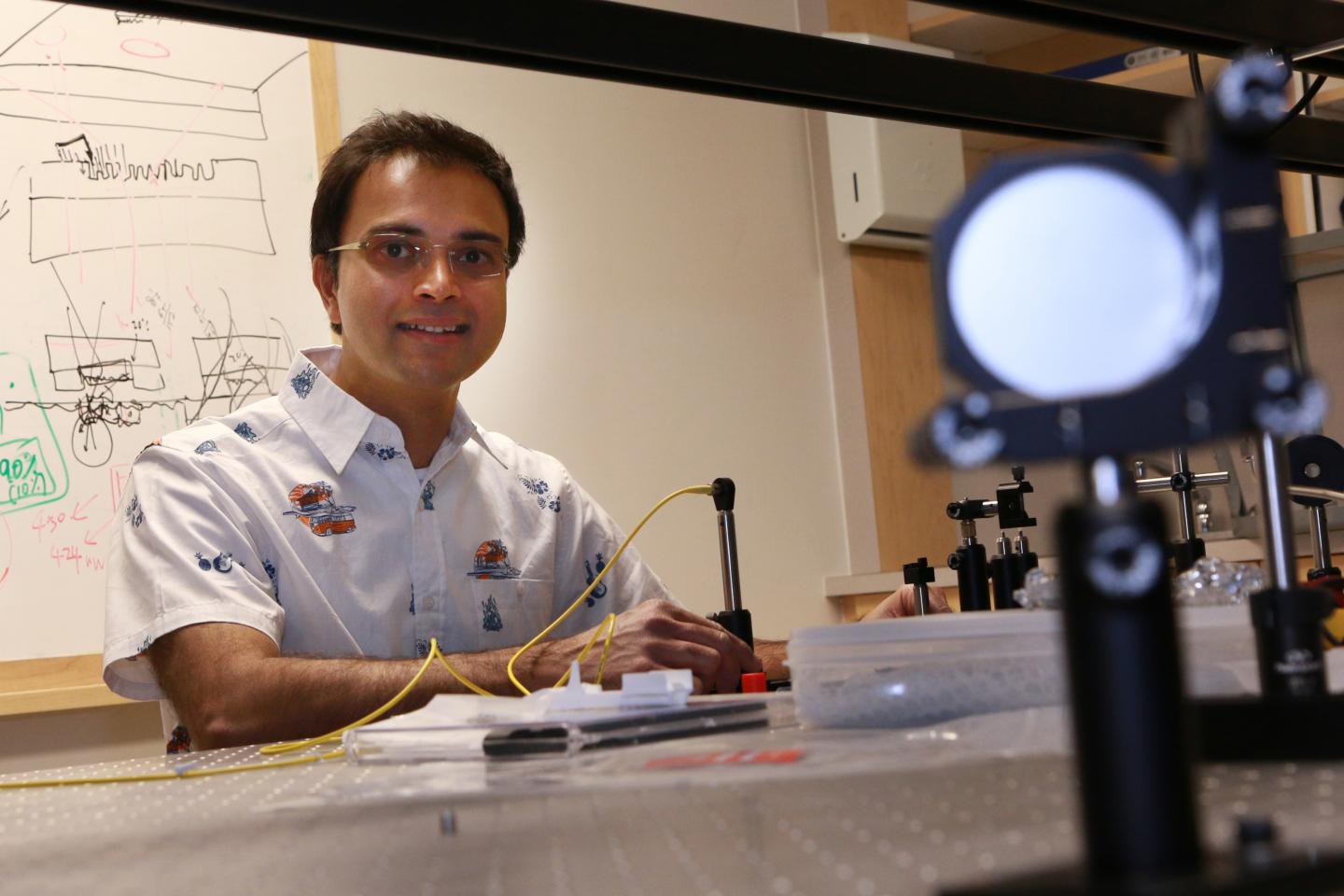

Menon supercomputes at the speed of light

Utah engineers take big step toward much faster supercomputers

University of Utah engineers have taken a step forward in creating the next generation of supercomputers and mobile devices capable of speeds millions of times faster than current machines.

The Utah engineers have developed an ultracompact beamsplitter -- the smallest on record -- for dividing light waves into two separate channels of information. The device brings researchers closer to producing silicon photonic chips that compute and shuttle data with light instead of electrons. Electrical and computer engineering associate professor Rajesh Menon and colleagues describe their invention today in the journal Nature Photonics.

Silicon photonics could significantly increase the power and speed of machines such as supercomputers, data center servers and the specialized computers that direct autonomous cars and drones with collision detection. Eventually, the technology could reach home computers and mobile devices and improve applications from gaming to video streaming.

"Light is the fastest thing you can use to transmit information," says Menon. "But that information has to be converted to electrons when it comes into your laptop. In that conversion, you're slowing things down. The vision is to do everything in light."

Photons of light carry information over the Internet through fiber-optic networks. But once a data stream reaches a home or office destination, the photons of light must be converted to electrons before a router or computer can handle the information. That bottleneck could be eliminated if the data stream remained as light within computer processors.

"With all light, computing can eventually be millions of times faster," says Menon.

To help do that, the U engineers created a much smaller form of a polarization beamsplitter (which looks somewhat like a barcode) on top of a silicon chip that can split guided incoming light into its two components. Before, such a beamsplitter was over 100 by 100 microns. Thanks to a new algorithm for designing the splitter, Menon's team has shrunk it to 2.4 by 2.4 microns, or one-fiftieth the width of a human hair and close to the limit of what is physically possible.

The beamsplitter would be just one of a multitude of passive devices placed on a silicon chip to direct light waves in different ways. By shrinking them down in size, researchers will be able to cram millions of these devices on a single chip.

Potential advantages go beyond processing speed. The Utah team's design would be cheap to produce because it uses existing fabrication techniques for creating silicon chips. And because photonic chips shuttle photons instead of electrons, mobile devices such as smartphones or tablets built with this technology would consume less power, have longer battery life and generate less heat than existing mobile devices.

The first supercomputers using silicon photonics -- already under development at companies such as Intel and IBM -- will use hybrid processors that remain partly electronic. Menon believes his beamsplitter could be used in those computers in about three years. Data centers that require faster connections between computers also could implement the technology soon, he says.

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?